Noah Graham/NBAE via Getty Images

Noah Graham/NBAE via Getty Images

Anyone reading this blog even half-heartedly knows how much stock I put into the player tracking statistics so wonderfully provided by NBA.com. Most of the base information used in the Player Breakdown series comes from a player's percentile placement compared to the rest of the league, along with the frequency of said play type, and from those baselines I extrapolate on what those numbers tell us. A trained basketball mind will tell you that every advanced stat out there has its flaws, and at the end of the day, observations on a player are much almost always more valuable than numbers like PER and RPM, which boil down a player's box scores into a value compared to the rest of the league. Unlike baseball, the other half of this blog, there are many different variables that play a role in how a possession ends, and numbers don't tell the whole story. Keeping the idea of qualitative observation in mind, the NBA signed an agreement with a company called Synergy Sports Technology way back in 2008, providing some of the services Synergy Sports offer to NBA.com, like play type statistics. It's not very clear on that page (and I don't feel like researching how they do this), but basically Synergy Sports tracks every attempt in a game, assigns it a play type, and tells us who attempted the shot, who defended the shot, and whether it was converted or not. These basic numbers along with a few others are crunched and spit out onto NBA.com, telling us how frequently a player attempts a certain play, how often they defend a certain play, how many points they scored from that area, and more. Instead of just knowing that LeBron James shot 49% from the field this season, we can look and see that he shoots 40% in isolation situations, 68% in transition, 44% when spotting up, etc. Essentially, these numbers provide a more qualitative view on basketball, something that we haven't really seen from statistics we now accept as commonplace. Even with the availability of these numbers, they have yet to be incorporated into new statistics on a large scale, so I figured I should tinker with the numbers a bit and see what happens.

The basic idea for what is about to follow is that we look at the average percentile (based on points per possession) a player placed in in the 11 offensive play types and 7 defensive play types provided by NBA.com and Synergy Sports and combine them to see what we get. The start of this project was pretty much me thinking, "What would happen if I averaged the offensive and defensive percentiles for a player?" Of course, being as ambitious as I am, the absolute first goal of this project was to create a new value-placing stat to replace PER. As quickly as I started, that dream died. Now, I'm not entirely sure what to make of this stat (I don't have a degree in Statistics), but I think it has potential. In the first phase of this project, I averaged the percentiles of 3 radically different players: DeAndre Jordan, LeBron James, and Stephen Curry.

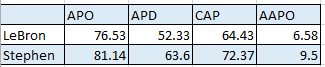

"Neat! What does it mean?" you are(n't) probably thinking! Well, APO stands for Average Percentile - Offense, APD stands for Average Percentile - Defense, and CAP stands for Combined Average Percentile. APO and APD were calculated by adding up all of the percentiles provided by NBA.com and dividing by how much types a player qualified for. For example, Steph Curry did not qualify for defense against the roll man, so his placement is not included. Qualification is simply playing 10 mins/game and garnering 10 possessions of that play type. CAP is APO + APD / 2. Complex, right? Since I'm not an elite coder and gathering those 3 player's info was tiring enough, I didn't really look at anyone else's numbers, but already a story is unfolding. Play type statistics will probably end up favoring players who "stay in their lane" on both ends, so to speak. Stephen Curry placed incredibly high on offense and was the best on defense out of the three according to these numbers, and that can be attributed to a multitude of reasons. A player like LeBron, for example. qualified for every category, and he did not score incredibly well in most of them, placing highest in things like transition and isolation play types. The fact that he qualified for more play types hurt his overall number, even though it was fairly close to Stephen Curry in the end. Another example would be DeAndre Jordan, a premier defender, receiving a 38.58 APD. This low score comes mainly from the fact that DeAndre qualified for placement in areas like isolation defense and defense off of screens, areas most big men generally don't do well in. Almost immediately after the numbers came out, I figured that perhaps looking at play type numbers aren't the best for measuring individual defense, and thus the search for good defensive metrics continue. Even so, the offensive numbers seemed pretty good to me, but I wanted to expand on them a little. NBA.com also provides frequency data, telling us how often a player executes a certain play type. I wanted to incorporate these numbers into the basic equation somehow, as I thought it might be more fair. I also didn't look at DeAndre's offensive numbers for this section, primarily because I found LeBron and Curry's numbers more interesting.

Now we see a new category: AAPO. This stands for Adjusted Average Percentile - Offense, as it looks to improve on the raw APO number. AAPD could definitely exist, but I wouldn't put too much stock into it considering the flaws in defensive play type statistics. The "Adjusted" part of the name comes from the fact that this equation accounts for frequency of a play type. For example, Stephen Curry placed in the 73rd percentile for transition offense, and it made up about 22% of his offense. The percentile number is multiplied by the frequency percentage to create a number more indicative of a player's rating in that area. Curry's raw transition percentile came out to 15.93. This same principle was applied to every play type the two players qualified for, and the product of said frequency/percentile adjustment was then averaged again by the number of categories the player qualified for. The number is based on how frequently the two attempted a certain play type and how many points per possession they score compared to the rest of the league, and a rudimentary score is created on the other side. Stephen received a score of 9.5, whereas LeBron received a 6.58. Draw your own conclusions from these numbers, as the scale is not out of 10 like one would think. If this equation was applied to a larger sample size, a more accurate conclusion could be drawn, but it took long enough to do just James and Curry by hand. I was pretty pleased with my work by this point, so of course I decided to see how much further I could go with these numbers.

Finally we see OVOR, the namesake of this article! What the hell is it? To be honest, I don't really know. Again, I don't have a degree in this kind of stuff, so I pretty much took the VORP equation (which is [BPM - (-2.0)] * (minutes played/3936) * (games played/82) for the uninitiated) and substituted BPM for AAPO. The VORP equation adjusts for how many minutes a player plays and how many games the player plays in compared to the total amount of minutes in a season and the total amount of games. The -2.0 was changed to -1.7, as according to basketball-reference, -1.7 accounts for offensive replacement level value and -0.3 accounts for defense. Applying these ideas on a wider scale would provide a more accurate measurement, but at the very least, even if these calculations are extremely basic, I think that looking past simple box score stats and exploring everything the new stats the NBA provides us is something worth looking into, preferably by someone more educated than I. Perhaps this wasn't the most successful venture, but hopefully it at least stimulated some thought.

Credit: NBA.com, basketball-reference.com